It’s November 1901 in Minneapolis. The Milwaukee Road Depot is a bustling hub of all manner of humanity. The train station’s imposing clock tower marks time for the multitude of travelers who rush to and from its tracks.

A few stick out among the derby-capped crowds. Passers-through, who are stopping in Minneapolis for a night or two, are easy to spot, rubbernecking their way down Washington Avenue, unaccustomed to the overstimulating sights, sounds and smells of a city so big.

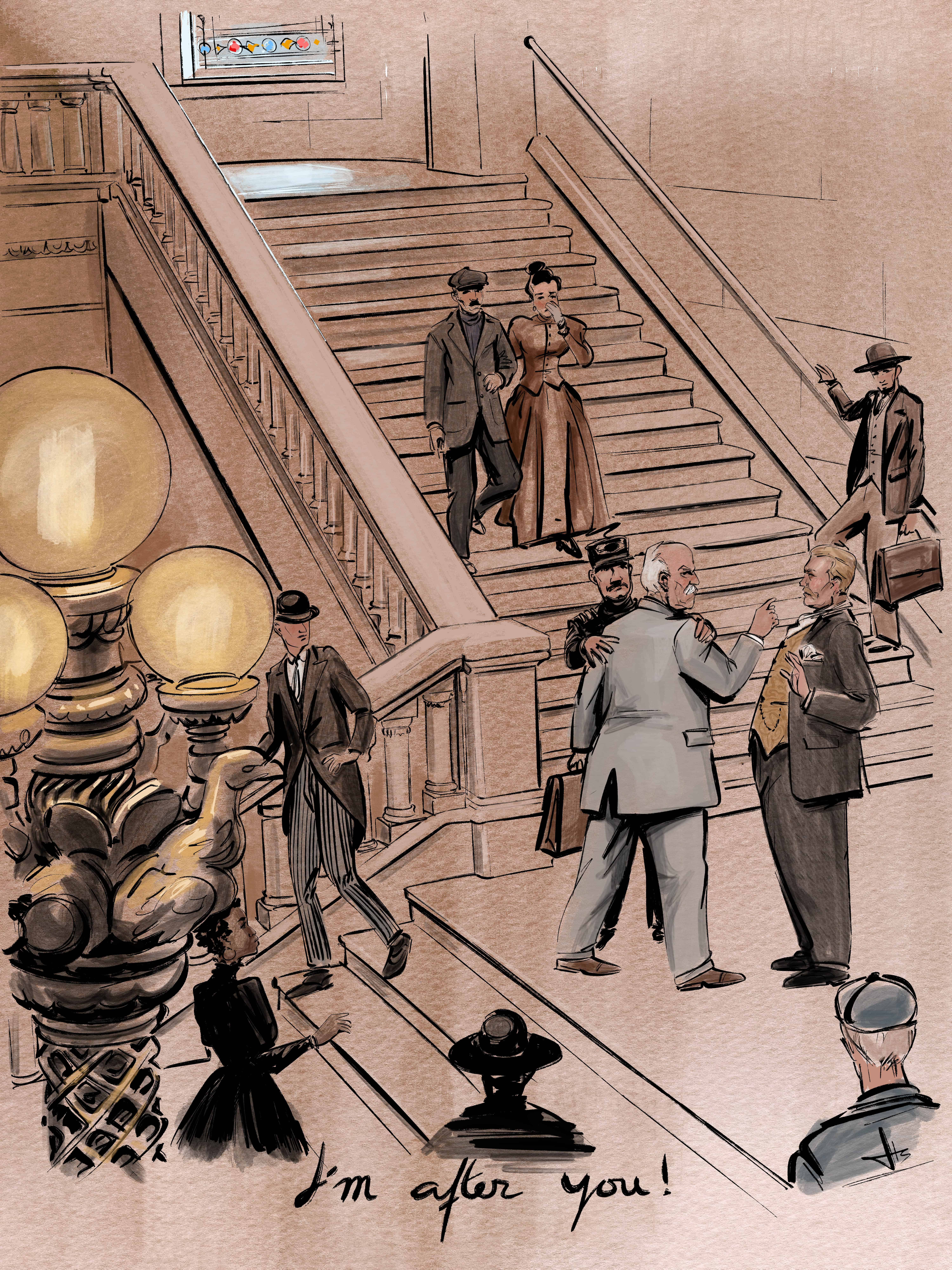

Perhaps they are first approached at a streetcar stop. A tip of the hat. A tentative handshake. “Are you new in town? Can I show you the sights?” A wide, warm grin. A friendly face in a foreign land. First, this well-dressed gentleman recommends a shared dinner, possibly at one of Minneapolis’s most popular establishments. It might be the Hotel Nicollet, the Creamery Restaurant and Buffet, or Schiek’s Palatial Place — which employs three French chefs to create luxurious meals for the city’s well-to-do. Minneapolis’s eight-story West Hotel on Hennepin Avenue is famous for its giant billiard room, where a drink and a cigar can be enjoyed after a vest-popping meal at their massive buffet.

Once dinner is complete, the gentleman, known among his ilk as a “steerer,” innocently suggests a game of stud poker to the unsuspecting rube. They soon find themselves at a table surrounded by fellow good-natured men, amiably betting (and all in cahoots, of course). The sucker does well at first, winning here and there, but it’s all manufactured to boost his confidence as the stakes grow higher. And once he’s all in, he loses, courtesy of the dealer’s deft sleight-of-hand. And if the sucker has an inkling that he may have been duped and threatens to fetch a cop, one magically shows up, ready to deliver some bad news.

“Gambling without a license, eh?” he says. “If you leave town now, I won’t haul you into Central Station.”

Soon the sucker finds himself being escorted back to the train station and told to go home. Hopefully, never to be heard from again.

Illustration by Hilbrand Bos

For an unlucky few, this would have been their introduction to Minneapolis. And this was just one example of the graft being conducted during Albert Alonzo “Doc” Ames’ notorious fourth term as mayor of Minneapolis. It was a city seized by vice, and the fix was everywhere. Doc was not only taking a cut from these shady card games, but he and his associates had their dirty hands in all sorts of illicit business; from shaking down houses of ill-fame to selling positions on the police force.

Doc had always been ambitious. His father had been one of Minneapolis’s first physicians, and he’d followed in his footsteps, eventually owning a thriving practice where he earned a reputation for treating those who could not pay. There was a motive behind it, however. With every complimentary splint or bandage, he knew he would earn a future favor.

As a Republican, Doc tried to win his party’s nomination for mayor in 1876, but when that went nowhere, he promptly switched allegiances and became a Democrat. Much of his future success would be attributed to his uncanny ability to sniff out opportunity, buoyed by a devoted cadre of blue-collar supporters known as the “tin-pail brigade,” who dutifully followed him to the polls. They were swayed by his charm, charisma and promises to alleviate their hardships.

Throughout his political career, Doc had some notable accomplishments. He spearheaded efforts to build the Minnesota Soldiers’ Home and championed an eight-hour workday. But there were also rumors circulating that the oft-inebriated Doc frequented gambling houses, saloons and brothels, and often conducted shady under-the-table deals. After two more terms as mayor, he lost the faith of the Democratic Party. The Republicans also wanted nothing to do with him. But Doc Ames still yearned for power.

Political enemies weren’t the only folks with whom Doc butted heads; he quarreled frequently with his own family, too. In the early 1890s, he drank and philandered his way across the city, which broke the heart of his wife Sarah, who had been a devoted wife and mother to their children Effie and John. One day, Effie witnessed her drunken, undressed father welcome a female patient into his office, and the situation rapidly escalated. Her husband William Rochford, who happened to be Doc’s business partner, gently tried to escort the woman down the stairs and out the door, but she tripped and fell. The woman sued Rochford, and when Doc testified on her behalf in the ensuing trial, the betrayal devastated Effie.

When Sarah tragically passed away, the family tension escalated. Doc refused to attend Sarah’s funeral. During the ceremony, he sat outside in his carriage with his feet up, smoking a cigar in a show of defiance and disrespect. And, in a cruel and bizarre twist, he then tried to abscond with Sarah’s body from Lakewood Cemetery. His antics accelerated the rift between him and his daughter, leading to permanent estrangement.

In the early 1890s the Minnesota State Legislature passed the nation’s first direct primary election law which allowed anyone from any party to vote in a Minneapolis primary provided they only voted once. While it was meant to reform an antiquated election system that allowed party insiders to choose their candidates, the new law backfired when Doc’s followers flocked to the polls to vote for him as the Republican candidate for mayor in 1900.

Doc not only won the primary but routed the Democratic incumbent James Gray in the general election, to the chagrin of many. And here is where the craziness really began.

First, the newly minted 58-year-old mayor hired his timid brother Fred as chief of police. He then fired half of the police force and replaced many of them with unqualified loyalists with questionable pasts. His choice for chief of detectives was a drunken bruiser named Norm King, who had a history of physical abuse against civilians. He made a bellicose seafood restaurant owner named “Coffee John” Fitchette a police captain. And his young medical assistant, Irwin Gardner, was responsible for extorting protection money from Minneapolis madams. Once collected, he would hand over a percentage to “the Old Man,” as Doc was known to both his friends and enemies.

The corrupt Ames administration went straight to work in January of 1901 and sailed along through that summer and fall, profiting from whoever the mayor’s henchmen could threaten, blackmail or con. It would take one of those out-of-town “suckers,” a stubborn Michigan logger named Roman Miex, to really set the wheels of justice moving. He had been fleeced in a card game on Thanksgiving Day by what was known on the streets as a “big mitt gang.” But instead of leaving town as he had been ordered, Miex spilled his story to a local reporter. The grift quickly made headlines, which led to an immediate outcry that set the Ames gang back on its heels.

It took a muckraking journalist named Lincoln Steffens to ultimately bring national humiliation to Minneapolis. While writing a series of scathing exposés on municipal corruption for McClure’s Magazine, Steffens arrived in Minneapolis in the summer of 1902 and quickly inserted himself into the unfolding events. He even managed to get his hands on a ledger that tied the bunco men (a group of professional con artists) to the mayor’s office. It was a damning connection that sent the rats in City Hall scurrying for cover. Steffens’ work, however, wasn’t the catalyst for the investigation. A grand jury led by businessman Hovey C. Clarke had been wading through evidence and testimony since late spring, and it eventually recommended criminal trials for the mayor and his cronies. Steffens’ “big mitt” ledger was the physical evidence necessary to solidify the charges. Soon, members of the mayor’s inner circle were tried one by one, convicted and sent to prison.

Not all, though, paid for their crimes. Doc Ames fled Minnesota, first hiding in Indiana and then in New Hampshire until a Hennepin County sheriff finally found him and escorted him back to Minneapolis in March of 1903. Now sickly and frail, Doc was prosecuted in a highly publicized trial, with his attorneys arguing that his greedy associates had taken advantage of his compromised mental state.

Doc’s first trial ended in a conviction but was overturned on appeal. More trials followed, leading to both hung juries and conflicted emotions by Minnesotans, who began feeling sorry for his prolonged legal woes. Authorities finally gave up their quest to convict Doc, and the once-disgraced former Minneapolis mayor lived out the rest of his life as a family doctor before dying in his sleep on November 16, 1911.

Ultimately, the “Old Man” never performed any redemptive act of atonement or experienced any epiphany. In fact, he stayed spiteful to the very end. He died with an estate of over $1,400 — and, in one final act of curmudgeonly vengeance — left Effie and John just a single dollar each.

Excerpted and adapted from Dirty Doc Ames and the Scandal that Shook Minneapolis (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2018).